Restoring Confidence,

1 Grain at a Time

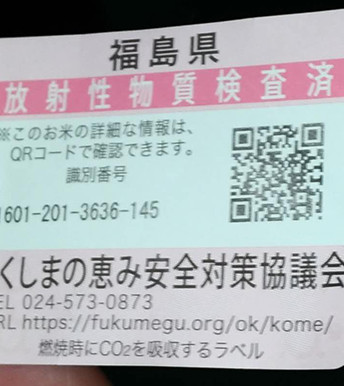

I was shown a demonstration of how the matrix barcodes are scanned from these labels in order to know where the rice was grown and its radioactive material screening results. The radioactive material screening results for all the rice is uniformly managed by a data management company using cloud storage technology.

For the screening results up until now, it is worth considering whether or not it is truly necessary to continue the screenings as-is. Since 2015, there have not been any cases of rice exceeding the standard radiation values.

In other words, the rice has fully met the safety standards, and given nothing but “all clear” results in inspections over the past two years. Meanwhile, the costs for these inspections exceed ¥5 billion each year.

Are the screenings still necessary? Everyone has a different opinion.

I had the chance to interview a farming couple living in Fukushima City. The husband’s name is Koji Kato, and the wife’s is Emi Kato. They are young for farmers, and have four children, aged preschool to middle school. I assumed they would think that the screenings were unnecessary; a waste of time and money.

Instead, Koji Kato told me, “They should continue. Better yet, they should keep going for 50 more years, leaving a record every year that the rice is safe. If we don’t do that, no one will understand the determination of Fukushima Prefecture.”

Raising their four children and dog, the Katos live in Fukushima, mostly producing the Fukushima rice brand Ten no Tsubu (“heaven’s grains”).

Compared to other, softer Japanese rice varieties, Ten no Tsubu has a slightly firmer texture.

In aging Japan, and particularly in Fukushima, whose population has seen a steep decline since 3/11, you rarely see a young farming couple like the Katos. For that reason, Koji gets a call whenever the news is covering farmers in Fukushima.

The couple runs Kato Farm. Both Koji and Emi used to be ordinary company workers, but seven or eight years ago Koji inherited rice paddies and farming equipment from his grandfather. “This is a good way of life,” he said. “You’re in touch with the sky, earth and paddies, and are free to choose what time to start and end work.

There’s no stress in interpersonal relations like you find at Japanese companies.” Emi, on the advice of her husband, was licensed as a rice paddy environment appraiser and rice advisor.

Slim and short in stature, she said frankly, “No matter how much I help out with farm work it doesn’t amount to much, so I figured I should make use of special skills.” Besides raising their children and taking care of housework, Emi also promotes Kato Farm and Fukushima rice through Facebook and other social media outlets.

Kato Farm’s rice paddies are now twice as vast as they were before 3/11. This is because the farmers in their area had grown old, and much of their land was left in limbo after the disaster. The Katos focused their attention on these tracts and, to prevent Fukushima’s farmland from gradually falling into ruin, decided to rent them.

Their paddies expanded little by little, and although rice plants began to sprout, the Katos’ income is far from ideal. Fukushima rice must regain the trust of consumers and regain its former status. It may be a long road ahead.

A variety of data on rice is published on Fukushima Prefecture’s website, and the 203 screening machines in the prefecture are running full-stop every day in order to measure the radioactive material data for all rice after it has been harvested.

The data shows that Fukushima’s rice is safe. Actually, a great number of restaurants in the Tokyo metropolitan area are using rice from Fukushima. This means that we are regularly eating delicious Fukushima rice.

Regardless of that, when consumers buy rice on the market, most of them still steer clear of anything from Fukushima.

According to a public opinion poll, 20 percent of respondents said they would never buy rice grown in Fukushima. The other 80 percent said they would buy it, or are waiting to see how things go.

“If 20 percent of people won’t buy it, how can we boldly introduce Fukushima rice to the remaining 80 percent?”

asked the Katos. “In order to show everyone the quality of Fukushima rice, we must continue screening every bag.”

Of course, the ¥5 billion it costs every year to fund the screenings comes out of taxpayers’ pockets.

As I left Fukushima, I saw an orchard along the way. Apples, pears, peaches and other fruit hung heavy on the branches. Fukushima is originally famous as a fruit-producing area.

Both Mr. Tanji and the Katos, who I interviewed for this article, said that they have never bought fruit since they were children. There are always relatives or friends growing fruit, so from the perspective of a Fukushima resident, buying and eating fruit seems unthinkable.

This is a naturally abundant and beautiful land.

Writer Du HaiLing

Chinese journalist living in Japan, Du is a reporter for “中文導報” (Chinese Review Weekly), a Chinese-language general newspaper issued in Japan (circulation of 80,000). Has published “女人的东京” (A Woman's Tokyo) and “无事不说日本” (Everything I Want to Say About Japan).