Restoring Confidence,

1 Grain at a Time

When I got off the train at Fukushima Station on September 22, my heart stopped when I saw the two Chinese characters for “Fukushima.”

My heart ached, I should say. Since the earthquake and tsunami of March 11, 2011, the two characters for Fukushima have taken on a sorrowful ring.

This despite the fact that it’s only 1 hour and 22 minutes from Tokyo on the shinkansen.

My first stop was the Crop Production Division in the Fukushima prefectural government offices. Speaking to Yoshihito Tanji, desk chief for the Crop Production Division, I was handed a set of papers and given a detailed explanation on why the prefectural government was screening every single bag of rice produced in Fukushima.

In October 2011, Fukushima Prefecture carried out a monitoring survey based on central government standards, and approved the shipment of rice for sale.

On November 16, however, rice exceeding the standard radiation value was detected in unpolished rice from the former Oguni-mura in Fukushima City, and press at the time went into an uproar. Fukushima Prefecture carried out an emergency inspection, but the word “radiation” was already etched into people’s minds.

In 2012, Fukushima Prefecture decided to start screening every single bag of rice. This meant that all the rice produced in paddies throughout Fukushima Prefecture, down to the last grain, would be screened for radioactive cesium. In order to produce the machinery that could handle the screening, bids were gathered from several domestic manufacturers.

Tanji said that, within four months, a new screening machine exclusively for rice was developed. The machines are extremely expensive, at approximately ¥20 million each. They are also extremely efficient, able to screen two or more 30kg bags of rice for radioactive material in one minute.

As a rice screening organization, the Fukushima Association for Securing Safety of Agricultural Products has been established at the prefectural level.

The association is comprised of Fukushima-ken Nogyo Shinko Kosha (the Fukushima Prefecture agricultural promotion corporation), JA Fukushima Chuo-kai (JA central Fukushima), JA Zen-Noh Fukushima (JA all-Fukushima agricultural co-op), as well as farm produce gatherers in the prefecture, consumer groups and other organizations.

Their work includes centrally managing the rice screening data and publishing the results online, as well as seeking compensation from Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) to cover the screening expenses.

There are also local councils at the regional level.

Fukushima Prefecture has a total of 38 such councils, comprised of municipalities, agricultural organizations, and produce gathering groups.

These councils are responsible for arranging where the screening machines will be set, printing the labels to be affixed to rice bags, carrying out the screenings and entering the results into a data management system.

So who pays all these rice screening expenses?

Including the costs for the organizations in the prefecture’s councils, where does the money come from? These are extremely practical issues.

Although compensation is being sought from TEPCO, the utility company cannot possibly cover all the costs. In reality, the expenses are generally footed by the central government; that is, taxpayer money.

The rice screenings in Fukushima City are done inside a company warehouse, where the task of hauling in the bags has been made easy.

At the screening location we visited, there were three of the expensive belt conveyor-type screening machines, with rice bags stacked up nearby. Each bag was 30kg.

Before it was equipped with a suction-type hand crane, the rice was loaded onto the machines by hand. Workers carried bags from morning through night, their backs groaning in pain.

Despite that, every single bag had to be screened. This was back in 2012, when the tests had just started. Although most farmers were elderly, they had to haul in 30-kilogram (66-lb) bags of rice for screening.

This was a huge burden on farmers. Each and every farm was visited in order to explain the situation but, despite being a seemingly simple task, hauling rice bags to the screening site proved to be a major undertaking.

In order for the screenings to be done properly, the prefectural government held a training course, and currently employs approximately 1,500 inspectors.

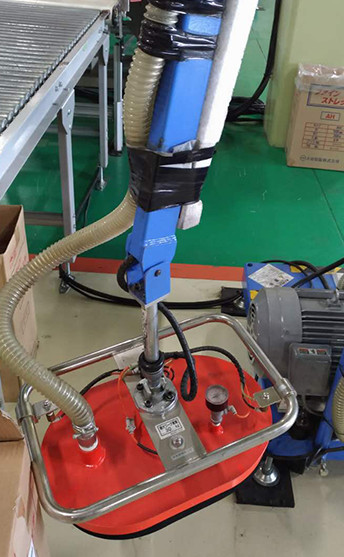

The workers at the screening site showed me a general demonstration of the screening process. Rice is loaded onto a cart and brought close to the screening machine, from which a suction pad-fitted hand crane lifts it onto the screening machine. By simply sticking the suction pad to each bag, any employee can easily lift rice onto the screening machine.

Barcode labels for the screenings are also affixed to the rice bags, with numbers showing where the rice was grown, the names of the farmers, and what number bag they are. Labels are printed according to the size of the rice paddies owned by the farmer, and any leftover labels are collected.

During screenings, the barcode labels are scanned and screenings conducted, as rice bags that passed are affixed with a label showing so. The labels are printed with the characters, “passed radioactive material screening,” along with a matrix barcode.